… and all it takes is for someone to show it to the world.

Pursuing a career in research involves more than working in a lab or sitting behind a computer all day, it also involves disseminating results and promoting the research. Within the scientific community, communicating research happens through the publication of papers and participation at conferences, but it is equally important to engage to the general public through outreach activities. Part of my PhD project includes participating in outreach, and I have to say I’ve quite enjoyed the projects I’ve been involved in so far (even though I’ve actually not done any outreach yet, just preparation of). Therefore, a bit of internet ramble on outreach.

1. What is outreach?

In this context, I guess outreach can be defined as raising awareness on a certain topic, such as science or academic research. It involves disseminating information about that topic to the general public and people outside the field to increase understanding and interest. Additionally, it could help engage children to the field. Outreach tools would include advertisement leaflets, newsletters, stalls or exhibitions in community centres, university open days, and the organisation of lectures and workshops at schools. Just to give a few examples.

2. Why even do research?

There is a discrepancy between how science is communicated through media and the actual reality of the research. Increasing the understanding of the topics of research, how research is done and how results are generally interpreted can perhaps help solve this problem. Additionally, outreach towards primary and secondary school pupils can perhaps shed a light on how research works and open up prospects of future studies and jobs. Research isn’t at all like the science you learn in school, and it can help get a few nerds enthusiastic about pursuing a career in science by showing them what’s in store.

3. Does outreach actually have an effect?

Let’s hope so. I’m sure there’s numbers out there, but I don’t know how to find them. And as I haven’t actually participated in any events yet, I can’t draw on personal experience. But even if all outreach does is raise awareness, I think that’s already a worthy cause. And if I can get even one child enthusiastic about science, I would consider that an accomplishment. “Did you know you can actually walk on water, if only you add enough cornstarch and turn it into a non-Newtonian fluid, isn’t physics awesome?”

4. My favourite outreach project

I guess it all started when I was 17 and went to the university open days. I already knew what I wanted to study, it wasn’t a hard choice, but had never considered anything further than the 3 year bachelor. Something a master student told me that day just stuck. She was studying nanoscience and when we asked her why, her answer was something along these lines: “It’s just fascinating. You know how the universe is infinitely large, well the nanoworld is sort of the same, just infinitely small.” And I could never get that out of my head.

An extract of my motivation letter to do my own master in nanoscience:

“I have always been fascinated in the aspect of infinity: the infinity of the universe, the infinite amount of atoms inside it, and the infinite amount of even smaller particles we’re only just beginning to understand. I have read several books on astrophysics in my spare time, for example “The Universe in a Nutshell” by Stephen Hawking, and have come to understand that there is a great analogy between the infinity of the universe and the infinity of what happens on atomic scale. The study of the infinitely small is a field that is particularly intriguing to me.”

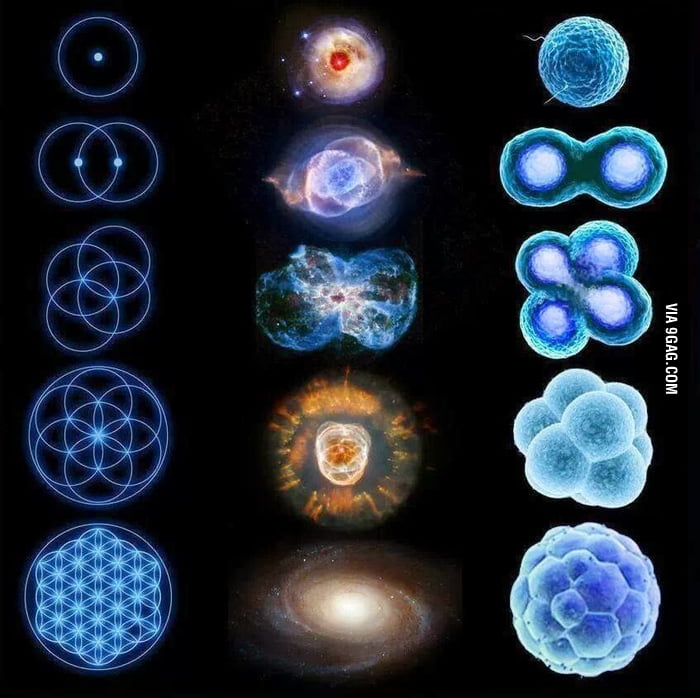

I got in and 3 years later I was asked to get involved in a project linking images from outer space to images of “inner space”, i.e. the world inside a cell. Think about it, haven’t you ever seen a picture of a cell and though that it looked like a far away galaxy? Or noticed that certain patterns and structures seem to reappear at every size dimension? It’s almost uncanny how images on such different size scales can look so alike. As an example, some time ago I came across the following image on my second favourite waste-of-time website:

I guess it suffices to say that I didn’t need much convincing to get into this project.

So, the Outer Space Inner Space (OSIS) project makes the link between the macroscopic world of outer space and the microscopic world as viewed through a microscope. We (a bunch of people from different schools within the University) are planning to convert the Mills Observatory seminar room into a platform for multimodal and immersive engagement. This will include a room-filling presentation screen to show images of the macro and micro cosmos, and space for workshops and exhibitions. It will also feature human-computing interfaces, ensuring that all audiences can experience and interact with the presentations. Within this framework, we also plan to organise activities within the International Year of Light. We have already started setting up an exhibition that aims to teach the general public about the principles of optics, and how this can be used to look at both things that are very far away as things that are very small. As my supervisor once pointed out: there’s not much difference between trying to look at something very small or trying to look at something very far away. A lot of principles in astronomy are being applied to microscopy as well, such as adaptive optics. And to throw in another quote, this one’s by Oliver Heaviside:

“There is no absolute scale of size in the Universe, for it is boundless towards the great and also boundless towards the small.”

I’m involved in a few other outreach projects as well, this blog might be considered as one of them I guess, though I’m not always – not to say hardly ever – talking about science or my life as a researcher. I’m involved in another project, in which we will try to organise a lecture series on the topic of “Science of Sci-Fi movies,” exploring the reality and feasibility of science and technology that appears in science fiction popular culture, and hopefully proving that some these nerd’s dreams have the potential to become reality. Finally, next month I will be participating in a “Bright Club” training, in my own small effort to prove that scientists can be funny too.

End of internet ramble.

———————————————————————————————

This post is based on an article that I’ve written for the PHOQUS newsletter that will be published soon, I have therefore plagiarised myself and apologise for anyone who has or will read certain sentences and ideas twice.

The quote in the title is attributed to Carl Sagan.